Chapter 10: Who Gets In? The Machinery of Democratic Elections

Chapter Summary Self-Study Questions Something to Consider Key Terms Case Studies Resources

CHAPTER SUMMARY

The most fundamental institution in a democracy is its electoral system, which consists of three basic elements: an electoral district size, a formula for allocating seats among the parties, and a type of ballot to be used by voters. The electoral system is a mechanism for turning votes into legislative seats, and this produces two by-products: a government (in parliamentary systems), and a party system. The democratic world is divided into systems that tend to produce majoritarian outcomes and systems designed to produce more proportional results.

Several criteria may be used to evaluate the operation of these systems, including variables that measure the fidelity of results to inputs, the degree to which governments are manufactured or supported, the filtering effects of the electoral machinery on the size and strength of the party system, and the ability of voters to vote and to understand the results of the system. The major electoral systems of the world are explained in some detail, with sample results presented and discussed critically and the evaluative criteria applied to determine strengths and weaknesses.

Something that is taken for granted in many localities is critical to the success of electoral systems—measures designed to ensure the integrity of elections. These vary from one jurisdiction to another but share the key feature of freedom from political influence. The election must be administered impartially by a body that is autonomous from the government, but accountable to the legislature at large.

SELF-STUDY QUESTIONS

Multiple Choice

(Answer key below)

1. Which of the following describes the process of gerrymandering?

a. Manipulating voting lists on behalf of candidates

b. Manipulating electoral boundaries for partisan advantage

c. Manipulating the outcome of proportional voting

d. None of the above

2. Which of the following is the mechanism for converting votes into legislative seats?

a. The voting system

b. The electoral system

c. The electoral vote

d. The political system

3. Which of the following is NOT a necessary feature of the voting process?

a. That it is accessible

b. That it is incorrigible

c. That it is incorruptible

d. All of the above

4. Which of the following is NOT a consideration when examining the transparency of an electoral system?

a. Whether voters understand the process of voting

b. Whether information on a voter’s choice is published

c. Whether electors understand how the final result of a vote is arrived at

d. None of the above

[qa cat=”ch10mcak”]

Short Answer

(Click question to reveal answer)

[qa cat=”ch10ssq”]

SOMETHING TO CONSIDER

1. The most important effect on the party system of the adoption of some form of PR in Canada would not be an increase in the number of parties but changes in their behaviour. What might these changes be?

2. What model of PR might work best with the other realities of Canadian politics? Consider list versus mixed-member systems, the size of a legal threshold, and whatever else might be important.

3. The strongest two arguments for FPP/SMP are that it produces a majority (single party) government and that it is an easy system for voters to use. The strongest criticisms of FPP/SMP are that it produces a majority (single party) government and that it is an easy system for voters to use. Which of these statements is more accurate?

KEY TERMS

(Click term to reveal definition)

[qa cat=”ch10kt”]

CASE STUDIES

1. For the Statistically Minded

A. CALCULATING THE EFFECTIVE NUMBER OF ELECTORAL OR LEGISLATIVE PARTIES

The Laakso and Taagepera formula for calculating the effective number of parties is as follows:

That is to say, divide 1 by the sum of the squares of each party’s share of votes (electoral parties) or seats (legislative parties). For example, if Party A has 50 per cent of the seats, Party B has 35 per cent, and Party C has 15 per cent, the effective number of electoral parties (ENEP) =

1 / ((0.5)2 + (0.35)2 + (0.15)2) =

1 / (0.25 + 0.1225 + 0.0225) =

1 / 0.395 = 2.53

(Alternative measures differ principally in the weight that they assign to minor parties.)

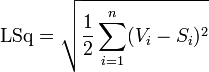

B. THE GALLAGHER INDEX OF DISPROPORTIONALITY

The Gallagher Index of Disproportionality, developed by political scientist Michael Gallagher, is as follows:

Or, in plain language, the difference between each party’s share of seats and its share of votes is squared, these squares are summed, the total is divided by two, and the square root of the result provides a measure of the disproportionality. If, for example, Parties A, B, and C received 50 per cent, 35 per cent, and 15 per cent of the seats, on the basis of 40 per cent, 30 per cent, and 30 per cent of the vote, respectively, a calculation of the disproportionality would be as follows:

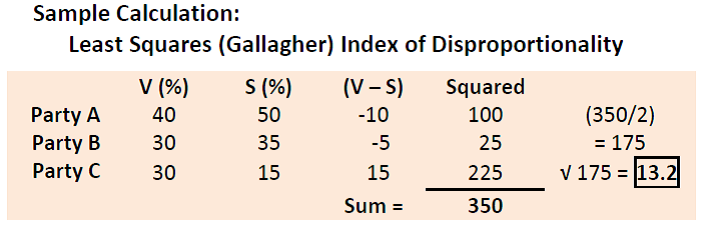

C. LARGEST REMAINDERS

For the mathematically inclined, a brief explanation of the largest-remainders and highest-averages methods used to allocate seats in multi-member PR districts may be of interest. The simpler of the two is the largest-remainders method, in which each party’s vote total is divided by a quota to determine its share of the seats. The quotas most often used are the Hare (dividing the number of votes by the number of seats) or the Droop (dividing votes by the number of seats plus 1). The figure below shows a hypothetical result in a 10-member district with 100,000 votes, distributing the seats according to the Hare and Droop quotas. The example illustrates that it makes a difference which method is used, the Hare quota being more sympathetic to the smaller parties.

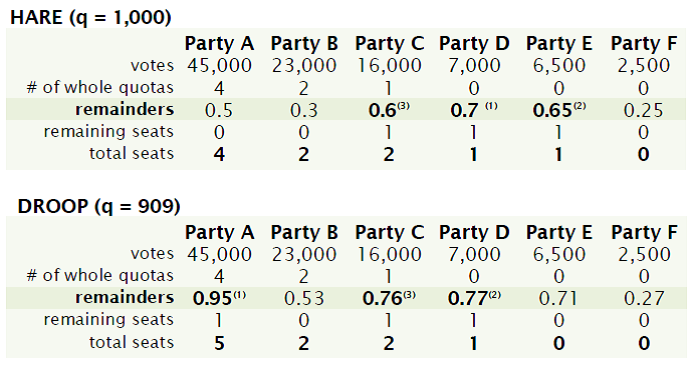

D. HIGHEST AVERAGES

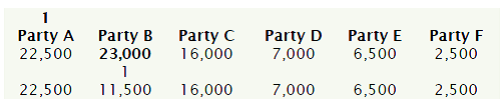

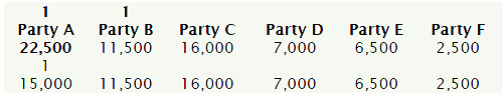

In the highest-averages method, a series of numbers (called divisors) is used to allocate the seats: each time a party is awarded a seat, its vote total is divided by the next number in the series of divisors. With the d’Hondt method, the divisors are (1, 2, 3, 4,. . .). Applied to our hypothetical result, Party A receives the first seat because it has the most votes, and its vote total is divided by 2.

When the party totals are compared, Party B now has the highest total, so it is awarded the second seat, and its total is divided by 2.

The votes are compared again and Party A’s total is highest; this time Party A’s original vote total is divided by 3.

The highest total now belongs to Party C, and because it is the first seat for this party, its total is divided by 2.

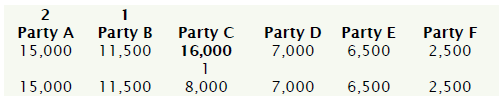

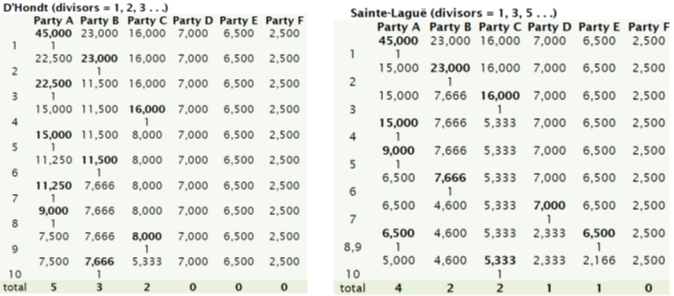

This process is repeated as many times as is necessary to fill the seats for the district. The complete allocation for this hypothetical result under the Hare system is provided below, as well as a result using the Sainte-Laguë set of divisors (1, 3, 5, 7, . . . ).

Here, too, it makes a difference which system is used: the final distribution under each is quite different. Consequently, questions of electoral reform in Party List PR systems often concern which method to use to allocate seats in the districts, and, where applicable, in the second tier of adjustment seats.

2. The Integrity of Elections

(Excerpt from an editorial by Vidar Helgesen, Secretary-General of International IDEA.)

The report of the international observers of the Russian elections [December 4, 2011] reads like a shopping list for those who wish to manipulate elections: denial of registration to political parties; disbanding of certain parties; heavy media bias; use by the governing party of State resources in the campaign; legal rights to assembly not upheld; lack of an independent electoral administration; inconsistent application of the law; undue interference by the State at all levels; and, last but not least, ballot box stuffing.

There are now more challenges than ever to the integrity of elections in the form of incumbency, violence, corruption, the penetration of politics by crime, the lack of women’s participation and low voter turnout. Added to these are the particular challenges of managing elections in countries in transition, such as Egypt, or in countries lacking any credible institutions, such as Libya. A common global challenge is the need to integrate new forms of technology and media in a way which bolsters, rather than undermines, the integrity of electoral processes.

—International IDEA Newsletter, December 15, 2011

(http://www.idea.int/about/secretary-general/integrity-of-elections.html)

RESOURCES

Chapter References

Duverger, Maurice. Political Parties. New York: Wiley, 1963.

EPRA (European Platform of Regulatory Agencies). Working Group 2: Political Advertising. Working Paper EPRA/2002/09 (October 2002). Electronic Copy

Gallagher, Michael, Michael Laver, and Peter Mair. Representative Government in Modern Europe. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995.

Green-Pedersen, Christoffer, and Peter B. Mortensen. “Issue Competition and Election Campaign Avoidance and Engagement.” Aarhus University. Aarhus, Denmark. N.P. (December 2010): 39 pp. Electronic Copy

Laakso, Markku, and Rein Taagepera. “The ‘Effective’ Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe.” Comparative Political Studies. 12.1 (April 1979): 2–27. Electronic Copy

Further Readings

Colomer, Josep. “The Strategy and History of Electoral System Choice,” The Handbook of Electoral System Choice. Ed. Josep Colomer. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. 3–78. Electronic Copy

____________. “It’s the Parties that Choose Electoral Systems (or Duverger’s Laws Upside Down).” Political Studies. 53.1 (March 2005): 1–21. Electronic Copy

Curtice, John. “So What Went Wrong with the Electoral System? The 2010 Election Result and the Debate About Electoral Reform.” Parliamentary Affairs. 63.4 (October 2010): 623–638. Electronic Copy

Hix, Simon, Ron Johnston, and Iain McLean. Choosing an Electoral System. London: The British Academy, 2010. Electronic Copy

Kelly, Richard. “It’s Only Made Things Worse: A Critique of Electoral Reform in Britain.” The Political Quarterly. 79.2 (April–June 2008): 260–268. Get Abstract

Leduc, Larry. “The Failure of Electoral Reform Proposals in Canada.” Political Science. 63.2 (December 2009): 21–40. Get Abstract

Lijphart, Arend. “Unequal Participation: Democracy’s Unresolved Dilemma.” American Political Science Review. 91.1 (March 1997): 1–14. Electronic Copy

Lundberg, Thomas Carl. “Electoral System Reviews in New Zealand, Britain and Canada: A Critical Comparison.” Government and Opposition. 42.4 (Autumn 2007): 471–490. Get Abstract

Orozco-Henríquez, Jesús. Electoral Justice: The International IDEA Handbook. Stockholm: International IDEA, 2010. Electronic Copy

Other Resources

Clark, William Roberts, and Matt Golder. “Rehabilitating Duverger’s Theory: Testing the Mechanical and Strategic Modifying Effects of Electoral Laws.” Comparative Political Studies. 39:6 (August 2006): 679–708. Electronic Copy

Sources for Electoral Results:

1. International Parliamentary Union (IPU) website

2. National government electoral administration websites

3. Wikipedia – provides English-language election results worldwide